The Graduate Crisis

How graduates can future proof themselves

On the week when A-Level results are announced, it is worth taking a long, hard look at what awaits the graduates of tomorrow. For decades, the link between academic achievement and professional success was relatively predictable: work hard, gain the right qualifications and secure a stable, well-paid job. That chain is breaking, and one of the forces snapping it is artificial intelligence.

The so-called AI tsunami is not a distant threat; it is already here, reshaping the graduate job market at a pace without precedent. In the past, automation targeted repetitive manual work. Now it is moving up the skills ladder into the heart of white-collar professions. The big four accountancy firms, PwC, Deloitte, EY and KPMG, have long been bellwethers of graduate employment. Yet even they are scaling back. KPMG, for example, cut its graduate intake by nearly 30 per cent last year.

The reason is obvious. Many of the tasks that once kept junior staff occupied, such as combing through financial statements, conducting basic legal research and summarising reports, can now be done more quickly, cheaply and often more accurately by AI tools. Law firms use algorithms to draft contracts and analyse case law in minutes. In finance, compliance checks and risk assessments are increasingly automated. In creative industries, AI can produce first drafts of articles, generate marketing campaigns or segment customer data, work that might once have taken teams of junior employees days to complete.

This disruption is not confined to one sector. Law, finance, media, HR and marketing are all feeling the tremors. While the technology brings efficiency, it leaves a human cost: fewer entry-level roles, fiercer competition for the positions that remain and a growing mismatch between what students are taught and what the economy needs.

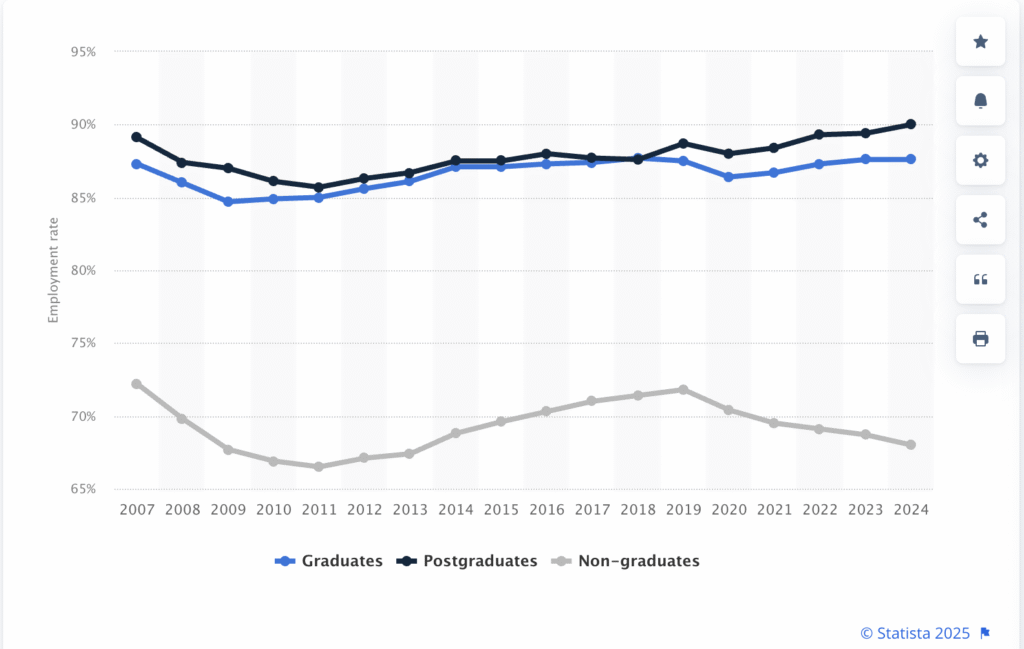

The uncomfortable truth is that the education system is struggling to keep pace. More graduates are emerging each year, many burdened with record levels of debt, yet they are entering a shrinking pipeline of traditional graduate programmes. Too often, they are ill-prepared for the rapid transitions and portfolio-style careers that will define the coming decades. At the same time, non graduate jobs are being eroded away even faster, as the gig economy takes hold amid a race to the bottom.

The highly specialised nature of the A-Level system can limit flexibility. A student who chooses narrow subjects at 16 may find their options constrained years later. To guard against this, young people should focus on developing universally valuable skills that cut across industries. Communication, collaboration and adaptability may sound like soft attributes, but they remain indispensable whether managing projects, pitching clients or leading teams.

Bill Gates has observed that certain disciplines hold enduring value: economics, computer science and mathematics. These fields do not merely open doors to multiple industries; they also develop problem-solving approaches that are hard to automate. Alongside these, vocational careers in engineering, medicine and other technical trades are likely to remain in high demand. Students should weigh not only what is popular today, but what will still be relevant when today’s tools have been replaced.

Perhaps most crucially, Britain needs a cultural shift towards entrepreneurialism. The era when most people could expect a job for life is fading fast. The ability to identify opportunities, take calculated risks and manage personal finances will be essential. Schools and universities must go beyond theory, teaching practical business skills from budgeting and marketing to negotiation and digital strategy. Even those who never run their own company will benefit from thinking like entrepreneurs in a fragmented job market.

The workplace of the future will be more dynamic, less predictable and for many, more precarious. Highly paid, long-term positions will still exist, but they will be the exception. In such a world, the safest strategy may not be to cling to the security of yesterday’s career ladder, but to build a ladder of one’s own. The next Bill Gates, Elon Musk or Sara Blakely may well emerge not from a conventional graduate programme, but from someone who sees disruption not as a threat, but as an invitation to create something new.

If Britain wants today’s graduates to thrive in the AI-driven economy, it must stop preparing them for a job market that has already disappeared and start equipping them to shape the one that is emerging.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for clear, timely insights on the political and economic trends shaping the UK labour market:

The data referenced above has been sourced from Vacancy Analytics, a cutting-edge Business Intelligence tool that tracks recruitment industry trends and identifies emerging hotspots. With 17 years of experience, we have a deep understanding of market activities in the UK and globally.

Want to unlock the full potential of Vacancy Analytics to fuel your business growth?

Book a 30-minute workshop with us and discover the power of data in shaping the future of your market!

p.s. By the way, if you are a fantasy football fan, why not join our league this season? With over 50 people already registered, we will be doing prizes for the winner and for the manager of the month if we hit 100+. Get involved!