The Deepening Youth Employment Crisis

Pitfalls of the proposed new policy framework

The crisis engulfing young people’s transition from education into work is deepening and the figures are increasingly hard to ignore.

Between April and June 2025, around 948,000 young people aged 16 to 24 in the UK were classified as NEET, not in education, employment or training, representing 12.8% of the age group. Before the pandemic, in the final business quarter of 2019, that number stood at 763,000. In raw terms, this is a 22% increase, a sign not of statistical noise but of a structural problem in the youth labour market.

In response, the government has announced a new policy aimed at long-term young claimants of Universal Credit: a guaranteed work placement for those who have spent at least 18 months neither earning nor learning. Refusal to participate could result in sanctions, the details of which remain under wraps.

Yet as with so many well-intentioned policy responses, the devil is in the detail, and the questions are mounting.

Would the threat of sanctions prove effective or merely counterproductive? Critics warn that removing benefits from already marginalised young people could risk pushing some towards illicit income streams or criminality, particularly if no realistic employment pathway is provided.

There is also the question of job matching. The prospect of a graduate in history, one of the degrees with the lowest transition to work rates, being sanctioned for refusing an apprenticeship in, say, plumbing or bricklaying raises ethical and practical questions. Does such a policy respect educational investment or render it meaningless?

Then there is the matter of business participation. Will employers be offered incentives such as tax breaks to absorb this new labour supply? Most companies employing 18 to 24 year olds — hospitality, logistics, retail — operate on thin margins. Without subsidies, many may simply not engage. Worse, in sectors not experiencing shortages, firms might opt to replace existing workers with cheaper government-subsidised labour.

And what of employment rights? The pending Employment Rights Bill promises stronger protections for workers from day one. Will young people on these schemes be afforded the same safeguards or be treated as second-tier labour? Businesses may be hesitant to extend full rights to individuals with no track record, a deterrent that could see the policy stall before it begins.

The deeper concern is that this scheme risks treating the symptom rather than the cause. The rise in NEET figures is not occurring in a vacuum. It reflects broader economic and demographic trends that have transformed the labour market over the past five years.

First, immigration. In the years following Brexit, the government authorised record levels of legal migration to fill workforce shortages, primarily in lower-skilled sectors. Many of these would historically have been filled by young British workers. In 2019, net migration stood at 270,000. By 2021, it had jumped to 488,000, and in 2023 peaked at 906,000. The result is an oversupplied entry-level job market in which NEET-status young people, 80% of whom lack a university degree, struggle to compete.

Second, automation. From supermarket checkouts to clerical processing, AI and robotics are displacing human workers. These changes hit entry-level positions first and hardest, the very jobs that once served as the gateway for young people into the workforce.

Third, taxation and regulation. Rising minimum wages, while morally commendable, have further narrowed the cost gap between human and automated labour. Meanwhile, the Employment Rights Bill, giving day-one rights to all employees, may disincentivise risk-taking by employers when hiring young, inexperienced workers.

These issues are by no means unique to Britain. Across the EU, the NEET rate for 18 to 24 year olds is estimated to be 12 to 14%, or around 4 million people. In Poland, more than 1 million Ukrainian refugees have entered the workforce since the war began. Even in a growing economy, this has created social and political tensions, leading Warsaw to propose revoking benefit entitlements for Ukrainian nationals.

Amid this, Brussels is lobbying hard for a youth mobility scheme that would allow up to 500,000 EU citizens aged 18 to 30 to live and work in the UK annually. Reports suggest the EU has even tied progress in trade talks, including now 50% tariffs on British steel exports, to acceptance of the proposal.

With a domestic youth labour crisis and a growing European one, any UK concession is likely to be fully utilised, pushing net migration further into the black.

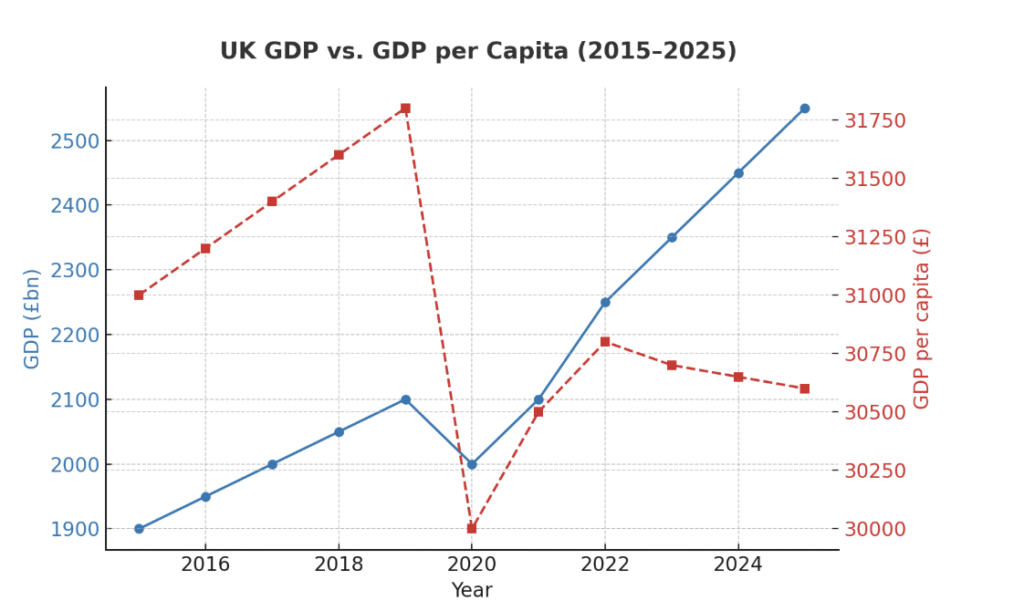

Labour faces a difficult calculus. On the surface, boosting the workforce via a mobility scheme could fuel headline GDP growth, but GDP per capita would remain under pressure unless accompanied by corresponding investment in skills, housing and services.

Without this, the danger is clear: British workers get priced out, businesses grow dependent on subsidies, and taxpayers foot the bill. A mobility programme could become little more than a corporate subsidy dressed up as a social policy.

Next move, Kier Starmer and Rachel Reeves.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for clear, timely insights on the political and economic trends shaping the UK labour market:

The data referenced above has been sourced from Vacancy Analytics, a cutting-edge Business Intelligence tool that tracks recruitment industry trends and identifies emerging hotspots. With 17 years of experience, we have a deep understanding of market activities in the UK and globally.

Want to unlock the full potential of Vacancy Analytics to fuel your business growth?

Book a 30-minute workshop with us and discover the power of data in shaping the future of your market!

p.s. By the way, if you are a fantasy football fan, why not join our league this season? With over 50 people already registered, we will be doing prizes for the winner and for the manager of the month if we hit 100+. Get involved!